If you would prefer to listen/watch the sermon instead of reading it, you can go right to it within our service by clicking on this link (be aware that this is Labor Day Weekend and we had a LOW attendance that day):

Last week, Paul used two metaphors to explain aspects of what Christians, and especially Christian leaders, should be about. He said we should be like soldiers, who don’t do what they want to do, but do what they are commanded to do. He also said we should be like athletes who have to compete according to rules and regulations spelled out for them. Today, we read about another comparison. Paul tells Timothy to “be diligent to present yourself approved to God as a worker who does not need to be ashamed, accurately handling the word of truth.”

What kinds of workers need to be ashamed? Workers who should be ashamed are workers who make it seem like they will do a job but then either don’t do it or else do it so badly it is as if they didn’t do it. In this case, the workers who should be ashamed are those who cannot accurately handle the word of truth.

I don’t want to focus on this part, not because it isn’t important, but because it is the kind of thing I say all the time. How does a worker get better at what they are doing? They practice. They put the time in. Nobody starts as a workman already at the level of a master. Everyone who gets good at anything does so because they have practiced it. Some people improve more quickly than others, but nobody improves without practice.

In the same way, if Timothy, or any of us, want to be a worker that does not need to be ashamed because we can accurately handle the word of truth, it means we need to practice. Nobody is good at that right away. The only people who are any good at it at all are the ones who have practiced. They have tried and failed a bunch of times, learning what to do and what not to do. If you are someone who hears the call to be this kind of worker and think to yourself, “Well, it can’t be me because I don’t know how to accurately handle the word of truth,” then the place you find yourself in is not to avoid handling it at all, but to practice it. You won’t get it right every time, but you will learn fairly quickly.

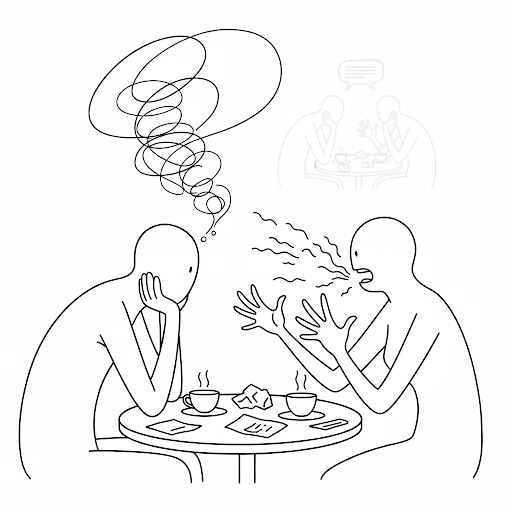

I want to focus most of my attention this morning on Paul’s advice for Timothy, and by extension all of us, to avoid worldly and empty chatter. I think that we can all probably agree with this advice, at least in the abstract. I should hope that, at the very least, we would all agree that if we are doing anything that counts as “empty chatter,” we would agree that we should certainly not seek to do it, and that our lives would almost certainly improve if we could avoid it. If we are chattering away with other people and the things that we say essentially mean nothing at all, it would be better to do without it.

Things get a little more complicated, I think, with the advice to avoid “Worldly” chatter. There are a few kinds of things that might fall under this heading. Sometimes, the New Testament will use worldly in a neutral way, to describe the things of this world, the stuff that is just part of getting by. That is, the adjective “worldly” might just have to do with being “non-spiritual.” A conversation about what to eat for lunch could be worldly in this way. Not good, not bad, just about meeting worldly needs.

The thing is, there is another kind of thing that the New Testament calls “worldly” and that is conversation that is either hostile to the spiritual or else neutral in a way that is distracting. This is complicated for a few reasons. If we are chattering about something that is overtly sinful, then it is clearly worldly in this sense. However, even if we are chattering on about something that is otherwise neutral but it gets in the way of our discipleship, it can become distracting and be worldly in this sense. I have some hobbies and I am happy to talk about them, but if that is all I talk about, then it means that I no longer have time to talk about what really matters. Even if we deal only with earthly matters, I have known marriages that have endured strain because one or both of the spouses are so deeply involved in their hobbies for such a prolonged period of time that they no longer have time to invest in their marriages. Even if the hobby isn’t bad in itself, it can become bad if caution isn’t taken.

Here is a question that it would probably be good for each and every one of us to consider: How much of my time is caught up in worldly and empty chatter? To say that it is probably a good question for each of us to consider is not to say it is easy. In fact, I think that it is hard, for a couple of reasons. I don’t know about you, but I generally do not label each conversation I have as “spiritual,” “worldly,” or “empty” at the time. There are conversations that I realize, after the fact, were mostly empty, but I didn’t notice it. Also, there have been times when I thought that the conversation I was having at that moment was empty only to realize, later on, that it was more important than I thought.

I would imagine that, for most of us, we think that most of our conversations are not worldly and empty chatter. We probably think that the conversation we are having is important in one way or another and that we should have it. Speaking for myself, I have a tendency to see the upside of most conversations that I have had. After all, I am a pastor of a church. Many of my conversations are about the congregation, about our faith, about our programming, about what to do or what to improve. Even if I have a conversation with someone that has nothing to do with any of that, I will still probably label it as “important” because it is important for me to maintain relationships with people that aren’t only ever about overtly spiritual things.

Also, I think that I (and maybe we all) have a tendency to think of all of our conversations as being important in one way or another. After all, if I admit to myself that some, maybe even many, of my conversations are worldly and empty chatter, then I would have to make some tough changes in my life. None of us like to admit it when we are doing something that is unhelpful. In some ways, I think it is even harder to admit that than it is to admit that we are doing something wrong. After all, doing things that may not be “wrong” in themselves but become wrong when we don’t keep them in check are always odd because we can always justify them to ourselves because they aren’t “really” bad.

There is, however, an even bigger reason why we might find it really hard to know just how much of our day, our week, or our month is taken up with worldly or empty chatter and that is because we don’t generally take stock of how we use our time. Most people tend to go through their lives without giving some of the details too much thought. If we have specific things to do, we pay a lot of attention to those things, but we don’t necessarily dwell on the other things. When we think about how we have spent our day, it is often the case that we remember mostly the things we did very much on purpose or else the unexpected things that took a lot of our attention. We don’t necessarily think about what we saw when we were driving from one place to another. If we greet someone on the street, we may not specially remember it later.

To be clear, this is not necessarily a bad thing. After all, I think it is hugely helpful for us all to have certain routines in our lives that help us to be more efficient than we would be without them. There are things that I get done every day, not because I make sure to decide to do them every day, but because I have built a mechanism into my life where it would be harder for me to forget to do them than it would be to remember to do them. There are any number of benefits of this kind of “flying on autopilot,” most noticeably that it means that we don’t have to make as many decisions because some of our basic needs are already decided, and so we can focus our energy on what is different each day.

The thing is, if we aren’t keeping track of things, we don’t know where we stand. I know that, speaking for myself, I had no idea what I actually ate until I made a point of actually keeping track of it. I could have given you some idea of what I ate, certain tendencies of what meals I made for myself, but I didn’t really know what choices I was making until I started keeping track of them.

What I was a bit surprised by is that, the moment I start keeping track of things, it changed the way I thought about them. At one point I set myself out to not change what I was eating, just keep track of it and then decide what to do. However, I found I couldn’t help myself. The moment I started tracking things, I found I made different decisions, even without a plan to do so. The moment I turned my attention to those details, I found that I made some decisions more and stopped making other decisions at all.

I think that, on one level, I knew that this would happen. I think that, so long as we are more or less ignorant of things, we can just kind of let things flow, let things stay the same, not get too worked up over things. Once we start deliberately paying attention to something, we immediately start to care about the choices that we or others are making. I think part of me always knew that tracking what I ate would immediately change my choices. In fact, I think that part of why I avoided it for so long was precisely because I didn’t want to change what I was doing and I knew that, the moment I paid attention to what I was doing, I would feel compelled to change. Not that someone else would make me change, but I knew I would put pressure on myself to change.

I had a professor in seminary whom I learned a huge amount from. He is one of my heroes in many ways. Nearly everything I have to say that has any value at all is because I learned it, one way or another, from or through him. I took every class I could with him. I even did an extra independent study with him. There was only one class he taught that I didn’t take.

It was called “Redeeming the Routines of Life and Ministry.” When he would tell us about the course, he would emphasize that life and ministry are not getting any easier. Clergy often take up any number of bad habits, not necessarily sinful things, but habits that, over time, reduce joy, satisfaction, and effectiveness. Sometimes it is because of the bad habit itself, but sometimes it is because the bad habit got in the way of a better way to live. The whole point of this course was to get students to take stock of their lives, think through what they were doing, why they were doing it, and build helpful structures into their lives for long-term thriving.

If you asked me at the time, the reason why I didn’t take the class is because I had to take other courses when it was offered and I just couldn’t fit it into my schedule, and that is at least partially true. The thing is, there was a time when it might have been possible to take it and then the schedule changed. I was so deeply relieved when it changed and I couldn’t take it because, I have to admit, I was kind of scared to take it.

The one thing that I knew for sure would happen in the course, because he told us, was that he was going to have us break down how we used our time into fifteen minute increments for a week or a month and then, afterwards, we were going to have to analyze it. I didn’t want to do that. I didn’t want to pay that careful attention to the way I spent my time, to the choices I made. I didn’t want to see what such an analysis would show me about my values and my priorities. I had an instinctive realization that I wouldn’t like what I would see and I also knew that, if I saw it, I would feel compelled to do something about it, and I didn’t really want to. You see, I don’t really like change any more than anyone else does.

I had reason recently to look over the historic questions asked of every Methodist pastor at their ordination, including me. The last question asks if we will observe certain directions. One of them is, “Be diligent. Never be unemployed. Never be triflingly employed. Never trifle away time; neither spend any more time at any one place than is strictly necessary.” I read or hear that and I think of all the time I have trifled away or how much extra time I spent in places or situations and I wonder how well I do with that.

I have to catch myself, too, because I instantly want to defend myself. Wesley himself took that aspect of things extremely seriously. He wouldn’t stay for a minute longer than he had to, to the point where I wonder if he should have spent more time in developing relationships. Something that we know in rural America is that the connections between people are shaped by every interaction with each other and if someone runs away as soon as possible every time they are anywhere, it says something. I have to deal with the fact that, even if we should be a bit more expansive than Wesley on what is “strictly necessary,” do we not all trifle away more time than we should?

Tomorrow is Labor Day which is often the date that we think of as being the end of summer. There is nothing magical about Labor Day. In fact, many people might argue that summer is over when school starts. I know many of the students think that way. Labor Day is the last three day weekend for school this year until Memorial Day. What that means is that most people, whose schedule is in any way tied to the school year, are finding themselves on the cusp of being in their normal routine.

I have made an appeal, off and on, over the summer, to encourage people to think about how they spend their time over these months where usual routines don’t tend to apply for everyone. I know that, for myself, summer seemed to fly by faster than ever before. Even if I wanted to keep a totally normal schedule, I couldn’t. I had annual Conference in June, followed immediately by an international family vacation. We barely got back and then we did church camp. We then had a few weeks of normality but then had Irish Fest and the Marcus Fair. Other people had similarly busy summers, although I am sure they looked a bit different.

As I say, I couldn’t possibly keep a totally regular routine, but there were things I made sure to do. I made sure to stay in my Bible, even when I was at conferences and camps, and even when we were in a foreign country. I made a point to stay on top of my daily reading from a gigantic theological work I am going through. I let some other things go, but I kept those things because I knew that, if I didn’t make them a priority, I could easily get to the end of the summer and have forgotten to do them at all.

How did your summer go? I don’t mean, did you have fun, although I hope you did. What I mean is, how did your faith and your relationship with God go? Summers go so fast and are so full that they can be remarkably helpful to look back on. I used to get bored in the summers when I was a kid. I haven’t been properly bored in what feels like forever. I feel like summers are a sprint for many adults, and those times where it feels like it is going a hundred miles a minute can show us stuff. What did we hope we would do but didn’t get around to? What forced itself to the front of our priorities? What do we wish, in hindsight, we did more of? What do we wish we did less of?

The reason why Paul warns us about worldly and empty chatter is not just because we have too much to do and not enough time to do it, and so any wasted time is too much. He specifies that “it will lead to further ungodliness,” and that kind of talk will “spread like gangrene,” which is no good. We need to cut out the bad habits and the poor choices we make for a bunch of reasons but part of it is because we need to be sure of who we are, what we are doing, and what matters the most to us.

We need to do that because, while we are all over the place, God isn’t. God knows exactly where he is, knows exactly who he is, and he knows what matters the most. If you wanted to grow your faith, how would you do it? Do you know what you are doing right now for your faith, or do you just do what happens to come your way? What would it take to increase the investment of your time in your faith by 1%? The only way to do that is to know what you are already doing, and the only way to do that is to keep track of it, one way or another. Once you know where you stand, you can make reasonable, intelligent, sustainable choices. If you don’t know that, you are flying blind.

Some people track their food, some people track their workouts, we should all be people who track our faith, not because we need to do so much to be loved by God, but because we cannot take a step forward if we don’t know where we stand. May each of us use this next school year as an opportunity to take that step, and encourage one another to not give up. Let us pray.

AMEN